Want to teach writing without a curriculum? You’re in luck – it totally can be done. Build critical thinking skills and raise thoughtful, engaged writers when you let go of your writing curriculum.

Some subjects are just plain scary.

Organic chemistry? Yikes.

Calculus? No thank you.

Metaphysics? Help (and snore).

They struck fear into our hearts as late high school and early college students, required courses we had to slog through in the mud. And then, there’s writing. It’s supposed to be simple, right? Start with letter formation, then sentences, then paragraphs, then essays. Presumably a much simpler process than exploring complex equations or theories.

Except it’s absolutely not.

For a lot of people, composition instruction is terrifying.

Parents, students, and even professional educators find it daunting without some sort of help. The focus turns not toward creating a culture of writers and thinkers, but toward finding the magic pill: there has to be a program or curriculum out there to guide us in our efforts, to prevent gaps in our children’s educational growth.

But here’s where the issue gets sticky. In order to lead others in their efforts to teach writing, the organic process – the culture – is broken down. It becomes a plug-and-play formula more suitable for baking than communication. The experience leaves everyone – both teachers and students – devoid of that critical, creative spark.

As I’ve walked through my own journey as an educator, both in the classroom and as a homeschooling mom, one aspect of composition instruction has become undeniable.

You really don’t need a writing curriculum. Here’s what you need instead.

So. What happens when you drop your writing curriculum?

Total. Chaos.

Ha. Just kidding.

I get the fear – I do. If you don’t have a curriculum to take you up the scaffold, how will you ever build the parapet at the top? Let me ask you a question, though, before you write me off entirely. What is your goal when it comes to teaching writing, and how best will that goal be achieved?

If your goal is to prepare a child for college and real word, I have some unsettling news for you.

The vast majority of college freshmen – yes, even homeschool graduates – end up taking remedial writing courses, even though they got all A’s in school. How do I know? I’ve been on both sides of the classroom, first as a high school educator and then as an adjunct prof. 75% of my college level students earned A’s and B’s in AP/IB courses.

I taught Developmental English – the course for students unprepared for English 101.

It wasn’t a failure on the part of previous teachers. It wasn’t their parents, nor was it the school system at large. Truth be told, it was the realization of a concept a favorite graduate professor once shared with me: the adherence to form over content in most secondary writing curricula kept a large number of first-year college students from succeeding. So trapped were they in prescriptive, formulaic writing, they couldn’t write their way out of a five paragraph paper bag.

This is why I advocate for dropping your writing curriculum.

Not because I’m some crazy, anti-authoritarian weirdo (I am Catholic, after all), but because most standard, common curricula are so focused on form you can’t get a word in. Isn’t that what writing’s all about?

When you drop your writing curriculum, you will bolster critical thinking

Current writing curricula box you into a prescribed form of writing. Each genre is taught in isolation, so you can’t see how form blends and moves. The strongest writing, the most forceful and evocative, uses elements of composition from across the literary spectrum. Take Thomas Jefferson, Martin Luther King Jr., or Alice von Hildebrand. Can you think of one five-paragraph essay among them?

Of course not, because it’s not real-life writing. Instead, it’s one our kids have to break out of and unlearn.

When you drop your writing curriculum, you will increase the comfort level

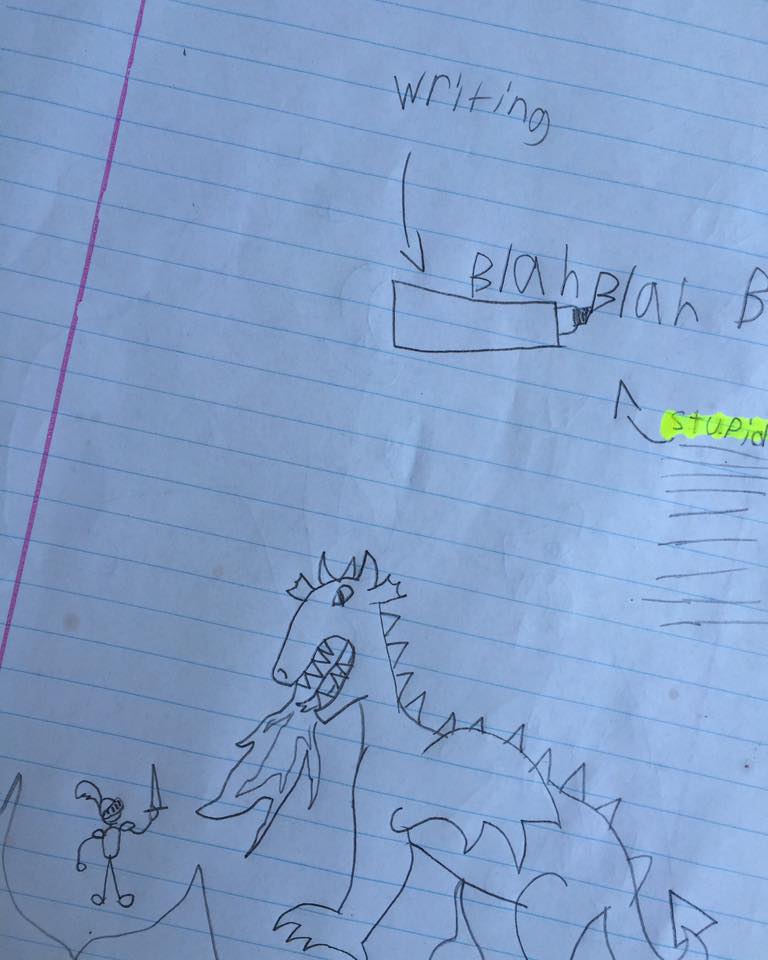

After my daughter’s first IEW class in co-op, I found this gem in her binder.  I probably should have been more reticent when it came to my own displeasure with the program, and yes – I did talk to her about the importance of respect and follow through. But what she clearly communicates in this image is a refrain that grew more serious.

I probably should have been more reticent when it came to my own displeasure with the program, and yes – I did talk to her about the importance of respect and follow through. But what she clearly communicates in this image is a refrain that grew more serious.

The program’s overt attention to inconsequential detail made her self-conscious. It wasn’t just damaging her writing – it was damaging her self-worth. Fortunately, the minute we quit the co-op, the more comfortable she became with writing. She has stories and articles aplenty, not a single one of them featuring a clincher or a dress-up. All she needs is a comfy place to write and a pencil as she’s golden. We’re all much happier, too.

When you drop your writing curriculum, writing will translate to real life

Think back to your high school math classes. How often did you complain about its irrelevance to your future, uttering the question, “When am I ever going to use this?” The same could be said for academic, curricular writing: there’s often only one purpose behind the pen. Students are writing for a grade, in isolation. Effective communication and the sharing of ideas are the lowest priority.

Instead of learning life skills, they’re meeting word counts in pursuit of an A.

Letting go of that mindset builds a new way of thinking. It opens doors for their writing they’ve not thought of before. Like math, writing is a skill they absolutely will use out in the real world. We owe them the opportunity to try it.

Clearly, there are benefits to dropping your writing curriculum. But the application can seem daunting at first blush.

How will you know what to teach, and when to teach it without a curriculum? Simple. You view it through a different lens.

How to Teach Writing Without a Curriculum

Step One: Make it Immersive

Writing should be a normal, natural part of your day. Start early with scribbles and lines for the littles; tell stories and record all the cute things they say. Leave notebooks and pencils in strategic places; build comfy writing nooks in the corner of a favorite family room. The more accessible and normal writing is, the better. It’s not a shock to the system if you’ve been doing it all along.

Step Two: Read and Discuss

At its heart, writing is a conversation. What better way to support the development of that skill than through conversation itself? Reading across the curriculum and from varying genres will not only expose a writer to elements of style, it will serve to develop necessary thinking skills. Through discussion, writers learn to ask questions and think critically about them, discovering not just what they believe (the thesis) but why they believe it, too (the defense).

Step Three: Make comparisons between styles, authors, techniques

In grad school, I took a creative writing course with the storied Alan Cheuse. A terrifying teddy bear of a man, Alan held court in a musty old classroom, insisting we read everything we could get our hands on first, before putting pen to page.

He was right.

Through the study of varied literature across authors and genres, I was better able to analyze the different types of writing and use that as a springboard for my work. I developed a stronger grasp of style and grammar through imitation; I found my own rhythm somewhere between Hemingway’s staccato and Plath’s command of verse. For our children, this task is second nature: they imitate so often through their play. They’ll build a singular voice and style by listening to the lilt of other literature and then imitating it. It’s much more natural (and tolerable) than copy work.

Step Four: Analyze your roadblocks

It’s true: some children (and adults, for that matter) don’t like writing. If you know the reason for the struggle you can find ways to work around it.

- Is it dysgraphia or fine motor difficulty? Use a keyboard instead of paper and pen.

- Is it the translation of thought to paper? Go for dictation or voice to text.

- Is it a lack of passion or boredom? Use a topic of great interest or a medium they enjoy.

It’s okay to be creative and use other forms of writing. Mobiles with short bursts of text or storyboards in comic format can be just as effective as long-form content.

Writing without a curriculum is a lifestyle, not a format. It’s a habit you develop every day.

Step out of the box and build an authentic culture of writers. You’ll let go of the fear and the frustration and emerge all the better for it.

For further reading and resources, check out:

Brave Writer (yes, it’s a curriculum, but it’s the most flexible and authentic that I’ve found)

Clearing the Way: Working with Teenage Writers

[rad_rapidology_inline optin_id=”optin_1″]

Enjoy this post? Read on:

Hands-on Writing with a Family Notebook

So happy I found this site! I am Catholic and started homeschooling one child last year, then added my second this year. Most of the homeschooling parents I have met so far follow other Christian denominations. The same is true for a lot of the resources found online. Thanks for helping to ease my anxiety wh n it comes to teaching writing!

In the article I see some good points, but in the end I realize that the daughter is frustrated because of her lack of writing skills and not with the curriculum she is placed in. She is not consistently capitalizing her sentences and her answers demonstrate that she didn’t even pay attention to class. No offense, but her writing was not witty, but sarcastic and ignorant. Wit would require that she has SOME knowledge about the topic she’s trying to “sass”. Kindergarteners know how to find the topic sentence but she doesn’t? I think the parent needs to admit her child may need some help with writing before she puts her daughter in programs that she’s not ready for. I don’t think parents should be so quick to ditch their kids writing curriculum after reading this article. I do agree however that people don’t need a curriculum to teach writing. Many of the worlds greatest writers didn’t use curricula to learn writing.

Hi, Millie. Thank you for your comment.

The assumption that my daughter was unable to identify a topic sentence was incorrect. She has been able to do so since, as you said, kindergarten. And no, that particular response was not witty; rather, it fit the second description I gave of anger and frustration – not frustration due to lack of knowledge, but frustration born of a program inhibiting her writing and requiring artificial, overt attention to concepts previously mastered. Perhaps I should edit the original post to reflect that.

I’m glad that specific curricula have worked well for you. The beauty of homeschooling is the ability to choose what works for you and for your children. For us, IEW is not that program – though I have the utmost respect for Mr. Pudewa. Again, thank you for your comment and have a lovely day.

Thank you for your reply! 🙂

Sorry if it seemed rude. I was trying to be blunt. Your assumption that I use IEW is incorrect. I don’t use it. I know of IEW because I’ve researched a good bit of writing curricula out there. I agree with you that it’s a beautiful thing that homeschooling allows you to choose which curricula and if any will be used to learn and study. My apologies for wrongly assuming that she didn’t know those things, I just made that assumption from the sample provided. And a sample is just that, a sample and not the entire picture. Thank you for sharing your tip!

You have a lovely day as well.

Hi Millie. To clarify, I only meant that I’m glad using a writing curriculum has worked for you. I did not mean to imply you used IEW.

Finding your blog post could not have come at a better time – definitely a God thing, so thank you for that. It was wonderful (!!!!) to hear that IEW did not work for someone else, it certainly did not work for us. I thought we were alone in that. I laughed out loud at your student’s responses because my (quirky) child’s work responses were very similar. As your student was, he certainly had the skills to complete the IEW assignments, he just wasn’t interested in the topics or the manner in which the information was presented. As well as the difficulty in being required to present his writing voice in an artificial manner, just to complete the assignment. I have been questioning (struggling over) whether it matters what he writes about as long as he is writing and learning various techniques. I’ve always thought that NO! it doesn’t really matter what the topic is. If it is something he’s interested in, he will enjoy writing about it and develop those skills…and that’s the point! However,, many of my homeschool friends use more structured writing programs and I was beginning to lean that way. Of course, we all need to do what is best for our own children. but it’s nice to know I’m not the only one doing something different. Thank you for the inspiration!

So glad you stumbled over here! And yes – we need to do what is best for our kiddos. You definitely aren’t alone!

As an English professor and homeschool mom, I completely agree with your assessment of a writing curriculum. I teach my students (at college and home) about Peter Elbow’s “Writing Without Teachers.” Too many students are taught to quickly focus on the nuances of writing instead of enjoying and gradually learning it.

This is an interesting take. My daughter will be in third grade next year, and I am wanting to move away from some starter/all in one curricula to cheaper, more adaptable DIY stuff. Language Arts is intimidating to teach for me–I taught math and science in the classroom before becoming a mom. If I want to do it free/cheap and write LA myself I need some tips for sure!

All three of my brothers are the AP kids you talked about who graduated high school while still writing rather poorly. All three improved immensely during college, though, so they eventually got it. I actually learned to write really, really well in AP classes. I credit my ability to write as a key factor in getting all of my college paid for through academic scholarships and grants. I’m starting to feel like the ability to write well as a young person may have much more to do with the underlying natural or innate ability that a child starts with rather than what specific approach we use to build on that natural foundation. It’s not a popular thing to say, but not every kid is going to be a phenomenal early writer no matter what you do as a homeschool mom.

I’m going to check out the Brave Writer program–thanks for the recommendation! I have seen it mentioned around but have done more looking in to Write Shop.

Thank you for sharing your journey! We are a traditional Catholic homeschooling family of one (two older in college). My 6th grader is a voracious reader. You would think that anyone who has consumed the entire red wall series, happy hollisters, hobbit, green ember etc etc would have a stored memory of enticing details that could be used to write his own story- but alas no, that is not the case. He loathes writing. We did start IEW, and he likes Mr Pudewa but starting with the lessons of creating stories based on pictures and having to form his own outlines did he start to have increased writers block and anxiety. I am a firm believer that the goal of homeschooling should be to foster a love of learning and NOT to score high on tests. I’m starting to question if we should continue with the program or try brave writer or go the route you suggested ( even though I have no background in writing as a retired nurse). BTW, I loved your daughters sarcasm, It reminded me of the comic strip circus. I can clearly see your daughter is very intelligent and God will have great plans for her quick wit!! It brought laughter to my son and I after sitting here for 2 hours trying to do a writing assignment! If you have any suggestions I have open ears!!

Hello, and thanks for stopping by. My first advice would be to foster an interest/love of writing in general. You might want to look through my writing archives – there are a number of fun activities in there, some specifically tailored to boys. Once he feels more comfortable in that regard, then I would probably move away from IEW and into something more flexible like Brave Writer.

Ultimately, the best way to help a child learn to add more detail is to teach them how to ask questions. So lots of critical thinking exercises (there are some in the writing archives) and looking at writing from the outside in (in other words, asking imaginary questions of the author of a particular piece; asking questions about his own writing).

I hope this helps a little – let me know if you have further questions!

Hello Ginny,

I just discovered your post and I found it very interesting. I have spent 43 years in the classroom , the last 20 leading English and I’ve always been a writer. Since retirement I’ve spent the last 8 years running an afterschool club and the biggest problem is Writing. As you said there is so much emphasis on form and so little on content. One of the problems I also encountered was that the children who come to me are not reading as much as they should so they’re not exposed enough examples of good writing. As I’ve encouraged reading and provided a wide range of reading materials I am beginning to see improvements in my present group. Thank you for this enlightening post.