Revision. For most people, it means one of two things:

- An unpleasant task in which one checks for correct grammar and spelling, then calls it a day

- An unnecessary (nay, evil) task which can be avoided if one does it right the first time

But really? Most people are wrong.

Now I’m not riding a high horse by any means. I’m guilty of the above, too, especially during my high school and college years. It wasn’t until my graduate experience with the Northern Virginia Writing Project that I understood the meaning of true revision.

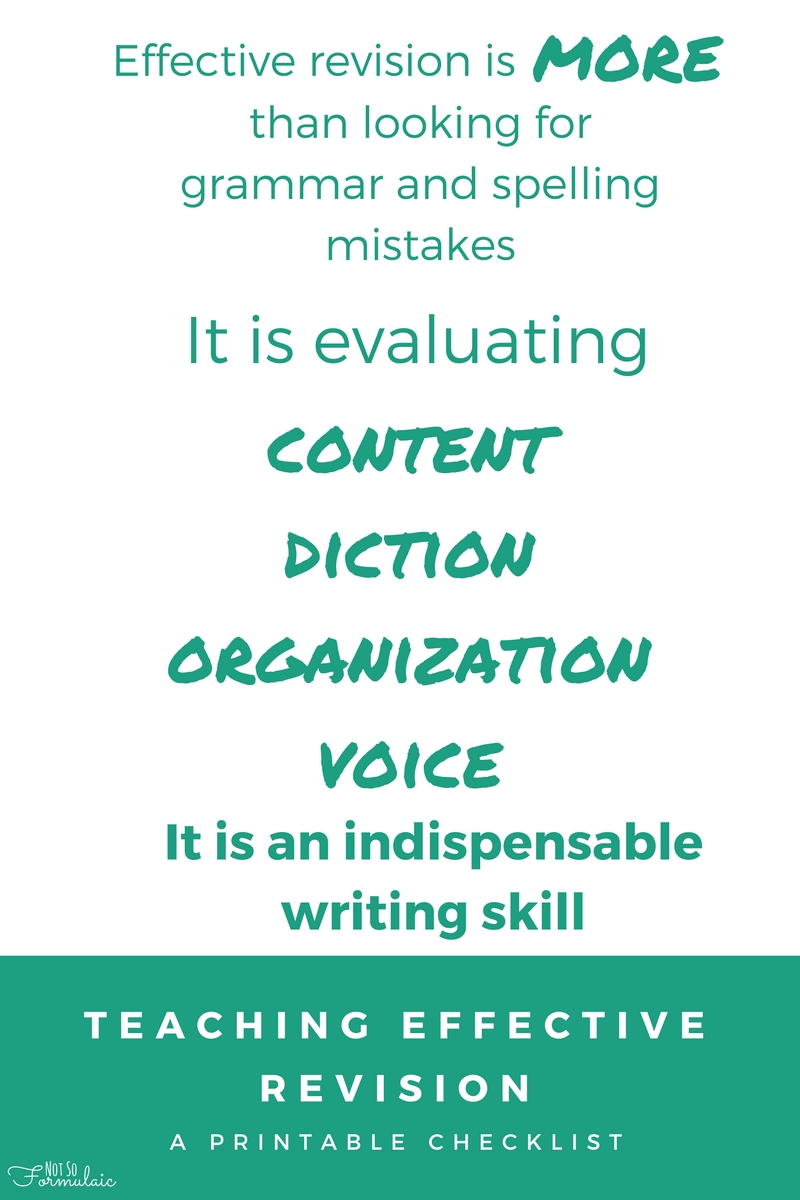

To revise means to look at your writing with a critical eye, one which evaluates a piece from all sides. It takes your work from ho-hum to knock-your-reader’s-socks-off. So not only does effective revision mean correcting grammar and spelling mistakes, it also means looking at the content, the diction (word choice), the organization, and the voice. It’s an indispensable writing skill.

But it’s not often taught in schools or writing curricula.

Why? Because writing is hard enough to teach. It’s not like math or science with their objective truths. It’s not even similar to history, really, with its facts, dates, and concrete events. Even the most well-intentioned and knowledgeable writing teachers assume the craft of revision will come along naturally as a writer’s skills grow.

But it’s not organic. It’s a skill that has to be taught.

How? With questions. The more questions a reader asks, the more she will uncover the areas in need of being addressed. Here is a list of questions I use with my children, my tutoring and co-op students, and my own writing to spur deep, effective revision. (If you like it, you can even print off this handy checklist here.)

Content

Nonfiction:

- What is the purpose of your piece? Have you accomplished that? How?

- Are you arguing something? If so, did you prove it? How?

- What would the opposing arguments be? What information do you provide to counter those arguments?

- Does your idea and its discussion make sense to someone else ( in other words, are you using reader based prose)? Or are there parts left out because your brain fills in the blanks (are you using writer-based prose)? Have someone read the piece to you out loud to help you figure this out.

Fiction:

- Does your piece invite the reader into your narrative? How?

- What theme or message have you crafted for your reader? How have you accomplished this?

- Are you using reader or writer-based prose? How do you know?

Diction (word choice):

Nonfiction:

- Who is your audience? In what way is your word choice appropriate for your audience?

- Are you using jargon (technical language)? If so, is it vital to your purpose? Have you explained what these terms mean, especially if someone outside your field will be reading?

- What sort of balance exists between complex and simple language? Are you using several words where one would suffice? Conversely, are you using complex vocabulary that limits your reader’s accessibility to the text?

Fiction:

- What is the balance between narrative prose and dialogue?

- How does your language build scenes? How can you expand important moments and condense less integral ideas, such as the passage of time?

- How does your language build characters? Do certain characters have specific patterns of speech? Do they use a specific dialect?

- Are you relying on direct or indirect characterization? How does your word choice reflect that?

- What is the balance between showing and telling? In other words, how much do you describe for the audience? How much do you tell them directly? Which one is more effective for your purpose, and why?

Organization:

Nonfiction:

- What type of organizational pattern are you using? Are you blending patterns? Should you blend patterns? Why or why not?

- How does your organizational pattern develop your idea or argument? Would a different pattern be better? Why or why not?

Fiction:

- What techniques have you used to develop your story? Are you narrating chronologically? Are there flashbacks? What point of view are you using? In what ways do these elements complement or detract from your plot line?

- What sorts of cues do you provide for your reader? In other words, how are you leading your reader to subtleties in your characterization? Theme? Conflict? Symbolism?

Voice:

Nonfiction:

- What is your attitude toward your topic? In what way do you reveal that to the reader?

- How does your voice impact your reader’s experience? Does it sway the reader? Distract? Encourage? Entertain?

- Do you have any unique stylistic features in the text? Does your language engage the reader or thrill him? If not, what can you do to fix this?

Fiction:

- What tone of voice do you want to foster? Why?

- How can you communicate that tone to your reader? Diction? Setting? Conflict? Characterization?

- Do you have any unique stylistic features in the text? Does your language engage the reader or thrill him? If not, what can you do to fix this?

Using this checklist is like going down a rabbit hole. The questions open up textual possibilities you might not have considered. Let them guide you as you make decisions about the direction of your piece and you’ll uncover a potent piece of writing.

[rad_rapidology_inline optin_id=”optin_1″]

Excellent tips!!! Very helpful post. An important thing I’ve been trying to teach my boys is that revision comes AFTER you are done with your first draft – not during. It can really mess you up if you try to have your revision filter on too much while you’re trying to get your thoughts down on paper.

I have really begun being critical of my writing in the past six months or so. Not in a bad sense, but in the sense of revision. I will say, revising my posts has oddly enough become one of my favorite parts of blogging!

That said, I’m definitely not an expert, and will be pulling up this article for future reference.

Thanks!

I love going back to fix my older stuff, too. After I get over cringing at how awfully written they are, that is 😉